When I do my year in photos project (every odd year since 2005) my worst librarian tendencies surface and I get somewhat obsessive about organizing them and making sure all the metadata is just so.

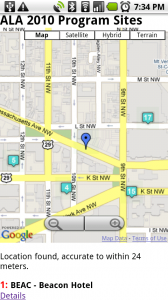

This year I’ve got a new wrinkle in that mix: geotagging. GPS data can be embedded in a photo, enabling all kinds of cool mapping stuff. Mostly I just like looking at where I’ve been this year in Picasa:

When I take the daily photo on my phone, all’s well with the geotags. The phone uses it’s GPS function and embeds the coordinates in the photo. But my phone’s camera isn’t amazing, and I try to use my Canon camera instead when possible. The Canon has no embedded GPS, so has no way to know where each shot is taken. Sure, I could manually place them on a map in Picasa or Flickr, but that’s tedious and inexact and requires a more detail-oriented memory than I usually possess.

I could also upgrade to a new point & shoot camera with GPS built in, but I’m not willing to face that expense right now. I wanted something that would tie my phone’s GPS into the camera. I didn’t expect to find much, but somewhat surprisingly there’s actually multiple options to do this:

First I found the aptly named Geotag Photos software. There’s two pieces: a phone app (for both Android and iPhone) and a desktop application. Turn on the phone app while you’re out taking pictures. It logs your position at regular (configurable) intervals. When you’re back at your computer, the desktop application compares photos’ timestamps with the gps log from the app. When there’s a reasonable match, it adds the tag to your photo. In my experience this works very well, but requires that I remember to turn the app on and get it logging before I snap a shot. That’s not a big deal for a day of frequent shooting, but for spur of the moment stuff it becomes an issue. I should note that the mobile app can be significant battery hog too.

Second is LatiPics. I’m a little astonished that Latipics has such anemic coverage on the web, because it’s pretty amazing. Latipics removes the separate mobile app from the equation, using only a desktop app. Instead, it pulls locations from your Google Latitude history. I already have Latitude turned on and logging, so it requires no extra effort on my part. Otherwise, the desktop application works a lot like Geotag Photos – it compares photo timestamps to my Latitude log, and adds geotags to the photos where there’s a match. This is pretty much my ideal solution (see the aforementioned lack of extra effort), but Latitude updates my location at somewhat random intervals and as a result doesn’t always provide a precise location for a photo. And of course, LatiPics requires you have Latitude history logging turned on and use a phone that can regularly update the service.

A third option is using an EyeFi SD card. I haven’t tried this personally, but don’t think it would suit my needs. EyeFi geotagging relies on examining your proximity to wifi access points, and so is less precise than a real GPS unit. And if you’re not in range of any wifi networks, it can’t do any tagging at all.

Geotag Photos and Latipics have different strengths and weaknesses. I find that I use both as a result: Geotag Photos for higher precision when I’ve planned taking pictures well in advance, and Latipics as a slightly less precise ‘better than nothing’ backup plan for spur of the moment opportunities. I should also note that Latipics is free, while Geotag Photos’ mobile app costs about 3 Euros.

(As a perhaps obvious final note: there’s clear privacy issues with sharing geotagged photos online. Mythbuster Adam Savage once accidentally revealed where he lived via a geotagged photo. Just be careful and use common sense.)