Apple loves to tout their 100,000+ iPhone apps. Android recently topped a respectable 20,000. These are both impressive numbers, but how often do we really need an app instead of the good old-fashioned web?

Apps lock up data and go against one of the central ideas and advantages of the open web – the ability to link between pages.

A user recently asked if our mobile app could add links to Worldcat items from our own mobile catalog items. I didn’t know the answer, but thought it sounded like a worthwhile addition if possible. I remembered seeing a Worldcat mobile interface a while back, and went looking for it once again. I found that Worldcat recently moved from a mobile website version to a mobile app version.

A mobile website is pretty self-explanitory. It’s a website formatted for a mobile screen that you load in a browser. It’s part of the web as a whole. A mobile app is more like any application on a computer – you launch it, do what you need to, then close it down. But mobile apps as they exist today are largely walled gardens, and don’t share data with each other easily (if at all). So while Worldcat has all their records very nicely displayed in this app, it’s impossible for our local catalog to link to them from the browser*.

Worldcat’s regular (non-mobile) site is very linkable. If I want to link you to The Mysterious Benedict Society’s record, I just have to give you this to click on. That’ll still work in a mobile browser of course, but the resulting page is clunky to view on a smaller screen. When OCLC has obviously gone to a lot of effort to get their data into a mobile format, it just seems a shame to ultimately lock it away from other developers inside an app.

And believe me, a native app for a phone takes a lot of effort. I originally tried to write one for the UNC catalog, but the fact that I’m not much of an Objective C programmer reared its ugly head and I had to abandon the effort. The return on the massive investment of my time and effort it would have taken to code an app just didn’t make sense. And a library catalog app wouldn’t even have any extra functionality over the mobile website catalog I ended up with. Our mobile site works on almost any modern smartphone, but if I’d somehow managed to bang out an iPhone app that app would work exclusively on iPhones. I’d have to start from scratch again to get the catalog working on an Android or Palm phone, and what about the countless phones that don’t run apps at all? They’d be left out in the cold.

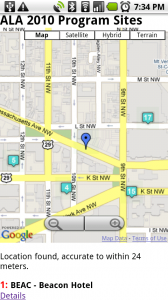

On the flip side, Apps certainly do have their time and place. They have greater access to the phone’s hardware than a browser, and can use things like the phone’s camera in ways that a mobile website currently can’t. But unless a hardware ability is central to an app’s purpose for being, I’d be hard-pressed to justify developing a full app instead of a mobile website. And now that many mobile browsers can access the phone’s GPS information, a webapp can actually do some basics of what were formerly hardware tasks. For example: I’ve become minorly hooked on the location-based service Gowalla lately, and Gowalla has no Android app – just a mobile website that can use the phone’s GPS to find where I am. It works really well. Full apps are also useful for offline tasks, since they allow caching of data & tools locally for use when there’s no connection to the web.

And apps do have an undeniable coolness factor. It’s a lot more impressive to say “Download our app in iTunes” than to give someone a URL to a mobile site.

But our library catalog & website don’t need a camera, and the very nature of a catalog is searching for information online – nothing can be stored locally in a way that makes any sense. Having a deliverable end product also wins out over the coolness factor with me, especially since I never could have completed the ‘cooler’ project in the first place 🙂

For the current state of the mobile web, I don’t think a mobile app’s advantages are enough for libraries. It’s important to get our information into as many of our users’ mobile devices as we can, and as quickly as possible. An app might come later; if the publishing world ever permits libraries to loan eBooks in a usable fashion, then sure a library eReader app would make sense to develop. But for now, when most of our mobile work is repackaging web data we already have into a new format, a mobile website is the way to go. It’s quicker to develop, works on more devices, preserves linkability, exposes our mobile pages for other developers to build on, and maintains the core functionality we’ve spent so much time developing for our non-mobile websites along the way.

(*As a side note, I did eventually dig up Worldcat’s old mobile web catalog. It still exists! But it doesn’t support direct linking either. This is another thing I’ve run into repeatedly – another argument/rant/post for another time.)